Reflections from an Activist-Turned-CEO

Wrapping up nearly two decades with White Ribbon Alliance (WRA), Betsy McCallon reflects on leadership, movement building, sector-wide “stuckness” and other lessons learned.

I joined WRA as a social justice advocate. I believed – and still believe – that systems change is the only sustainable and scalable solution to address deep inequalities present in societies around the world. Having grown up in a community where nearly half of girls were pregnant or moms by the time of our high school graduation, often forgoing their dreams and aspirations, I felt deeply that securing women’s bodily autonomy was one of the most important ways to help realize gender equality. My understanding of the lack of value placed on girls and women’s lives deepened after working with grassroots activists in central American and sub-Saharan Africa. Maternal mortality – the primary focus of WRA at the time – was a stark indicator of this inequality, both generally and grossly more disproportionately for some women based on their race or ethnicity, age, social and economic status, gender identify, or the geography in which they lived. So many organizations at the time were stuck in a top-down charity model that did not resonate with my community organizing and people-led advocacy experiences. WRA was doing things differently by galvanizing a grassroots network of activists to create local, national and global change. I was excited to join an organization that saw itself as part of a broader movement for women’s health and rights.

Movement Building

Nearly 20 years later, many more organizations refer to themselves as “movements,” and there is a reasonable debate about whether those terms themselves are contradictory. Generally, movements are defined by the short or long-term goal that unifies those who are a part of it; they tend to be organic and accountable to the goal, not an organization. Organizations often make incremental change with accountability for the organization as a key goal. Organizations are drawn to the movement framing – including many corporations of late – because it feels authentic and dynamic, rather than rigid, risk-adverse and compliance centric. Movements evoke important images of activism and key turning points in history, whereas organizations can evoke images of dinosaurs or ships – becoming extinct or very difficult to turn. Successful organizations, however, often look more like movements with the formal organization serving as the machinery to support the movement. In reality, movements are comprised of many different organizations and individuals playing very distinct roles within a broader, and often messy, big tent.

There are many factors that make movements (and organizations) successful – leadership is one of them. What brings people to a movement in the first place is fascinating – and essential – to understanding, and realizing, leadership success. Finding the right place within a movement is also important as the sense of belonging and collective ownership are key to weathering inevitable internal and external struggles. In the case of White Ribbon Alliance, the drivers, motivations, and backgrounds of its leaders and members are as diverse and varied as the geographies in which we live. For some, it is a deep personal connection to specific issues – for example, a relative dying in childbirth or a near-miss experience themselves – that compelled them to get involved or start a WRA chapter. For some, it is the scale of change that brought them in, such as midwives who felt their impact would be limited to the individual women they directly support unless the whole system were to change. And for others, it is more about the how: bottom-up, grassroots mobilizing and campaigning to change the status quo and address inequality, which was my pathway into WRA. What that means in practice is that WRA leaders come from significantly different backgrounds, education, training and lived experiences. This diversity is an asset for a movement.

While WRA’s organizational structure has followed some standard conventions, such as having a CEO role, it has never had a top-down, hierarchical structure with a figurehead leader. Instead, the movement has been comprised of many leaders, each of whom embody some of the most important traits, together forming the package that is critical for success:

- Lived experience and personal motivation

- Ability to articulate a vision and framing of the world we want, as opposed to the many challenges we face, and to see future trends and tipping points

- Sets bold goals, recognizing they will only be achieved with collaboration from many

- Willingness to show up and do the boring things; to be clear and realistic

- Welcoming of new ideas and perspectives, and values relationships

- Skilled at the art of reinvention – always looking for new and different ways to increase impact

- Agility and recognizes the need to adjust and try new things without losing sight of the goal; comfortable with risk and uncertainty

- Resilience – recognizes, acknowledges and deals with criticism, adversity and disappointment, acts on feedback and bounces backs

To be clear, I did not and do not embody all these traits, and yet I carried the extremely privileged title of Chief Executive Officer. I questioned this role – and how to continually earn my place within the movement – nearly every day. Others within the movement around the world called on me to use the position of privilege – as a white, American woman with a CEO-title – to be at the “table” to help set expectations and shift power. Acutely aware of the artificial separation between “Global North” and “Global South,” the persistent colonial structures and norms, and the overwhelming “solution privilege” and white saviorism concepts that abound, I tried to respond to this mandate to sit at key tables by pushing the conversation – sometimes as a broken record – with many of the traditional actors and within the system, to be about true people-led local solutions and leadership.

The Global Health Cabal

Some of my peers did not have the time to sit at these global, process-heavy tables and asked me to be the representative so they could get on with their important work driving change nationally and sub-nationally. They also recognized that resources and support for their work would only come if it was visible to those with power and influence and saw this as an important part of the puzzle. I also needed to carve out space for other leaders, often by pushing for speaking opportunities on global platforms and then passing them on, so they could be seen and heard. In some ways, this distorted system often bonded us together. We tried to leverage all avenues to make change, working inside and outside the system. The ownership and sense of belonging to the movement was the fuel that kept us going. At other times, this was highly deplorable, especially when my presence opened doors and got an audience with influential people that my colleagues couldn’t access in their own countries. Or when I was asked to basically handpick the designated “country” leader who should meet or speak in a high-level global forum. The reoccurring examples of the “proximity to whiteness” – as activist Tian Johnson so eloquently reminded us at an accountability event last month – were awkwardly swallowed as part of the development sector rules of engagement. We believed that we had to be at the table in order to flip it.

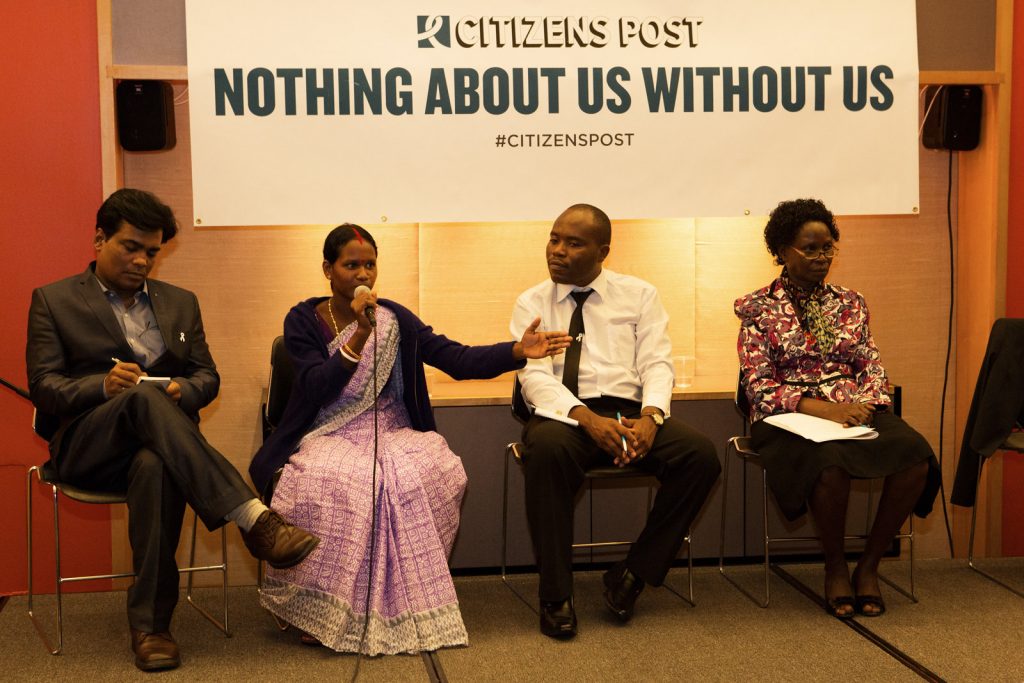

Photo 1:Aparajita Gogoi Photo 2: Angela Nguku

The Projectization Trap

There were additional challenges that limited us. The periods of least impact for WRA were when we fell into the trap of projectization. Donor demands from “priority countries” to “priority outcomes” narrowed our focus. Mobilization functions became subsumed by implementation. We also had a huge push for measurement (M&E) to attract funding by demonstrating quantifiable impact that resonated with donors, such as policy changes. In the advocacy space, there is often a debate about attribution versus contribution. For WRA members it was bigger than that: policy change simply was not the end game of our movement’s shared goals to see opportunities, experiences, and outcomes for girls, women, and newborns growing and changing. This “professionalizing” and “focusing” turned us into advocates for hire. The consequences of this projectization were significant. Alliances shut down. Staff burned out. Members lost interest and saw WRA as a competitor or new groups did not see an easy pathway to engage and participate.

As a leader of an organization within a movement, this is sometimes scary. The desire to reign it in or control messaging must be checked. But the most amazing things that happened during my tenure were when I let go; when I supported from behind. The scale and reach of our movement was strongest when we rallied around a shared end goal, not a prescribed path on how to get there. From Stories of Mothers Lost, to citizen hearings taking place around the world, to the What Women Want campaign, my best weeks as a leader were when I learned about a success after it had happened. When an idea born or borrowed from across the Alliance came to fruition. When trust and flexibility translated into tangible change.

Looking Ahead

FINALLY, there is significant recognition – at least in the rhetoric we now hear – across the sector that power and resources need to shift toward decolonizing global health, and that must happen to address inequities, in all their forms and in all geographies. That is why we must investment in movements – and movement leaders – rather than projects and institutions.

I am excited for the next chapter for WRA, and for my own. I have learned – and continue to learn – so much from other women leaders of movements and coalitions around the world who are doing things differently. Leaders who value trust and equity above organizational success or individual ego. Leaders who are rejecting conventional organizational structures and practices and challenge others to do the same. Leaders who are building new tables and forging solidarity alliances instead of trying to shift the sometimes intractable power structures. And leaders who will not be silent about the racism and patriarchy that continue to persist within the health and development sector.

And through all of learnings, I am both proud of and humbled by the farewell reflections of WRA leaders across the globe who characterized my leadership as passionate, determined, unflappable, and focused on creating opportunities for others. I know I won’t be remembered as the “face” of WRA and to me that is the best legacy I could ever wish for.

By Betsy McCallon

Betsy McCallon joined White Ribbon Alliance in 2004 and served as CEO from 2012 to 2021. She was responsible for facilitating the strategic direction, creating a unified vision for the Alliance, and mobilizing tools and people to deliver it. Betsy contributed to the growth of the alliance from a loose network to a driver for change at local, national, and global levels to advance reproductive, maternal and newborn health and rights and gender equality. Betsy is a champion for people-led accountability and transformative funding.